Don’t Panic When You See Green Chicken Poop

I do not have children, so I cannot pretend to know what it feels like to study a baby’s diaper with concern and curiosity mixed together. But I do know what it means to watch droppings closely, because when you raise chickens long enough, poop becomes one of your most reliable sources of information. People…

I do not have children, so I cannot pretend to know what it feels like to study a baby’s diaper with concern and curiosity mixed together.

But I do know what it means to watch droppings closely, because when you raise chickens long enough, poop becomes one of your most reliable sources of information.

People laugh when I say that, but it is true. Chicken droppings tell you more about health than feathers or egg count ever will. Color, texture, frequency, and smell all matter.

Over the years, I have learned what is normal on my farm, and that knowledge usually keeps me calm.

What Normal Chicken Poop Looks Like on My Farm

On a healthy day, chicken droppings come in a few predictable forms. Most are brown with a white cap of urates on top. Some are softer after a long drink, while some are firmer after a night of rest.

Every so often, you will see a cecal dropping, darker, pasty, and stronger smelling. That one often worries new keepers, but it is completely normal.

Because I watch these things daily, my eyes notice changes immediately.

The Morning Something Looked Wrong

Yesterday morning, when I walked past the entrance of the Rhode Island Reds coop, I saw something that stopped me.

Right near the doorway were two droppings that were clearly green. Not just tinted, but noticeably green. I stepped farther inside and saw more of them scattered among the usual brown ones.

My stomach tightened. Then, as if to make sure I did not miss the point, I watched one Rhode Island Red hen stop, squat, and drop a fresh green poop right in front of me.

That was the moment my mind went somewhere it probably should not have gone so quickly: disease, infection, and even virus.

I ran through names and worst-case scenarios faster than I care to admit. I told myself not to panic, but I also did not ignore it.

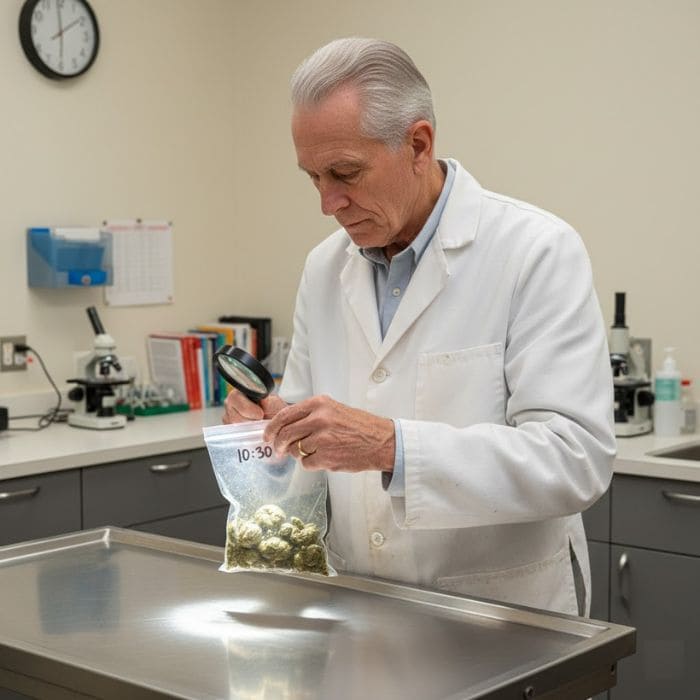

So I collected a fresh sample, sealed it in a plastic bag, labeled it with the date and time, and got into the car.

The nearest veterinarian station that handles poultry is not close. It lies in the northeastern part of Ohio, well over an hour’s drive from North Hollow.

The road there cuts through long stretches of farmland and small towns, and by the time I arrived, I had replayed every possible outcome in my head at least twice.

The Vet Visit I Almost Didn’t Need

The veterinarian was an older man, tall, with silver hair and hands that moved slowly but confidently. His coat was clean but worn at the edges, the kind of wear that comes from years of real work, not a desk.

When I explained what I had seen, he listened without interrupting, nodding occasionally.

He took the bag, examined the sample closely, then asked me questions in a calm, measured way.

“Any drop in appetite?”

“No.”

“Any birds isolating themselves?”

“No.”

“Heat recently?”

“Yes. A lot.”

He smiled then, not dismissively, but gently.

“Your chickens are fine,” he said.

He explained that green droppings are very often linked to diet, especially when chickens consume large amounts of vegetables or greens. Chlorophyll passes through the digestive system, and in hot weather, increased water intake makes the color more obvious.

He showed me what he was looking for, texture, smell, consistency, and pointed out what was not present.

There were no signs of infection. No mucus. No abnormal odor. No indication of systemic illness.

The Thing I Had Forgotten to Connect

As he spoke, it suddenly made sense. All week, because of the heat, I had been replacing part of the flock’s usual greens with fresh vegetables to help them stay cool. Lettuce, cucumbers, zucchini, melon rinds and water-heavy, fiber-rich food.

I had changed their diet deliberately, and then forgotten to connect it to what I was seeing on the ground.

The vet reminded me that chickens process food quickly, and their droppings reflect that speed. What you feed today often shows up tomorrow.

What He Told Me Actually Matters

Before I left, he made something very clear. Color alone does not diagnose anything. Context does. Green droppings become concerning only when paired with other signs.

A bird that is quiet, withdrawn, not eating, or losing weight. Droppings that smell foul, contain mucus, or remain watery long after diet and weather stabilize.

Changes that persist without explanation deserve attention. Changes that arrive alongside heat, vegetables, or increased water usually do not.

He told me that experienced keepers often panic less, not because they care less, but because they have learned to read patterns instead of isolated details.

When I returned to the farm, I walked the Rhode Island Reds coop again. This time, I watched without fear.

The birds were alert, busy, and steady. Green droppings mixed naturally with brown ones, exactly what a vegetable-heavy week would produce.